Tamsen Wojtanowski

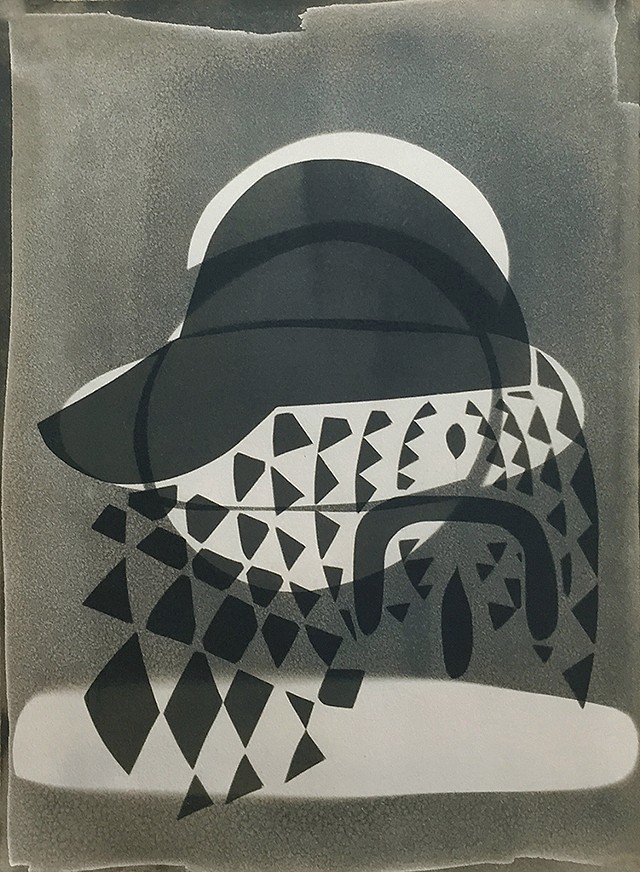

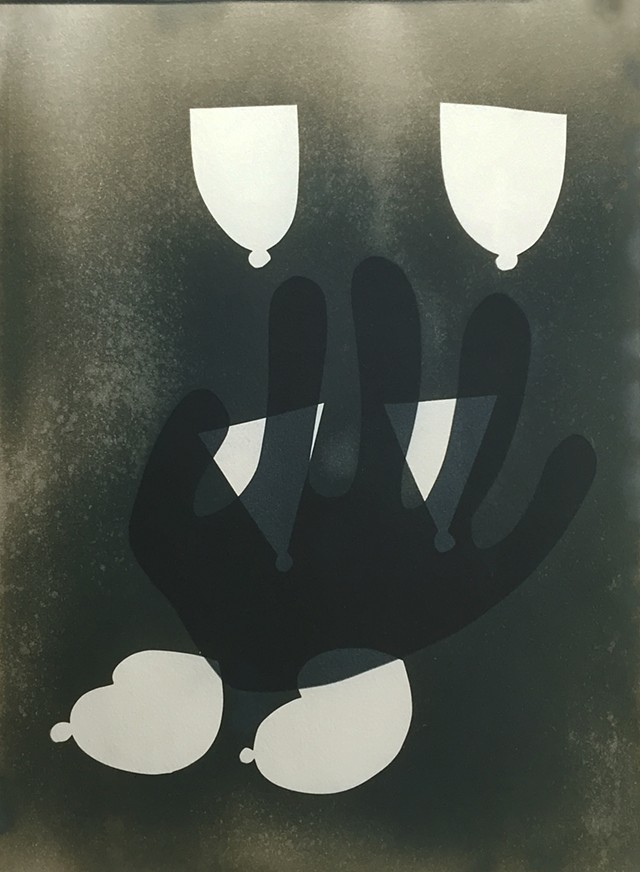

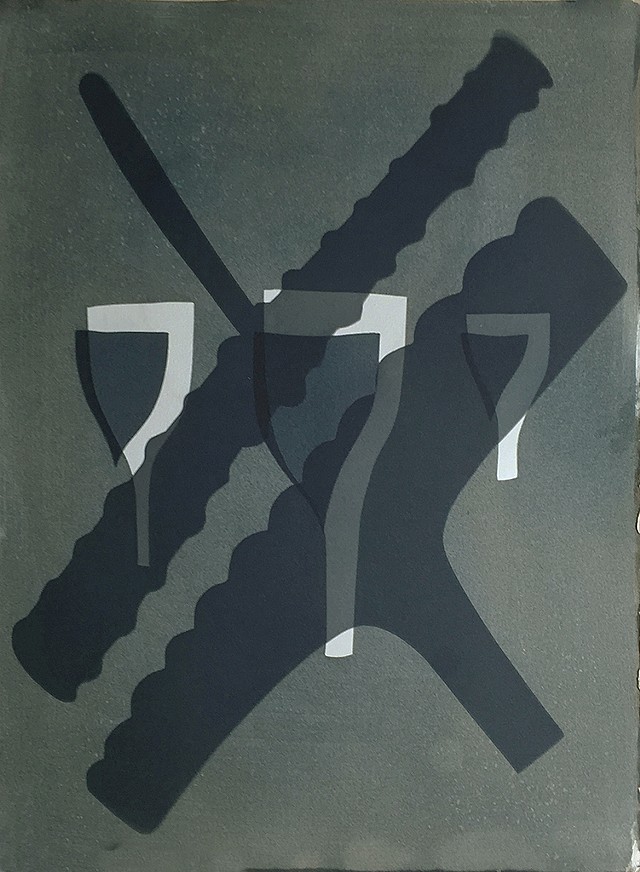

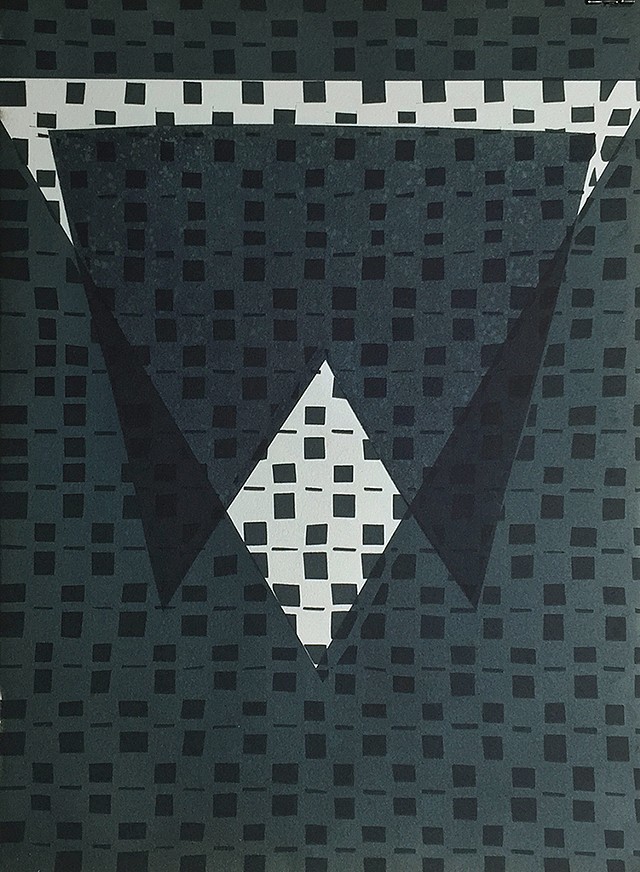

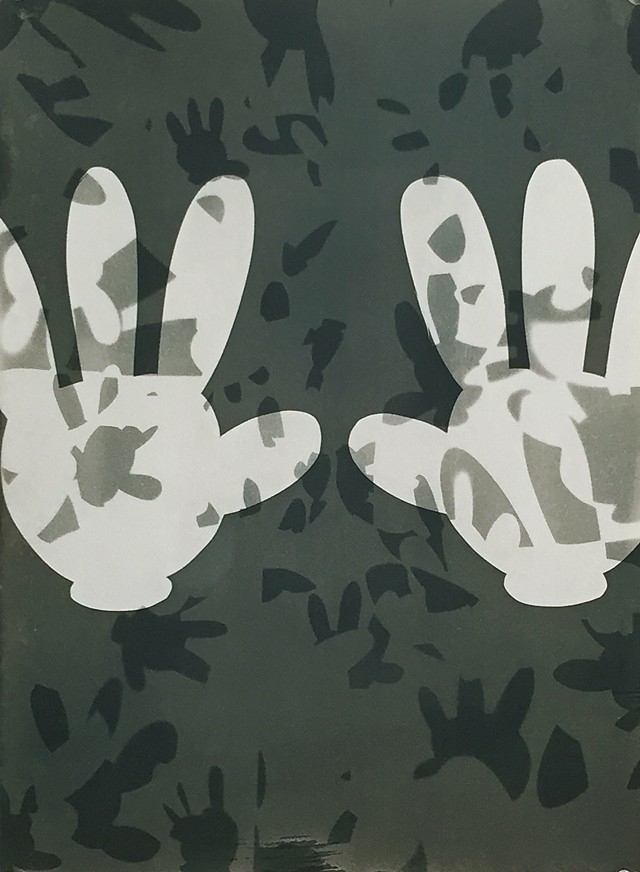

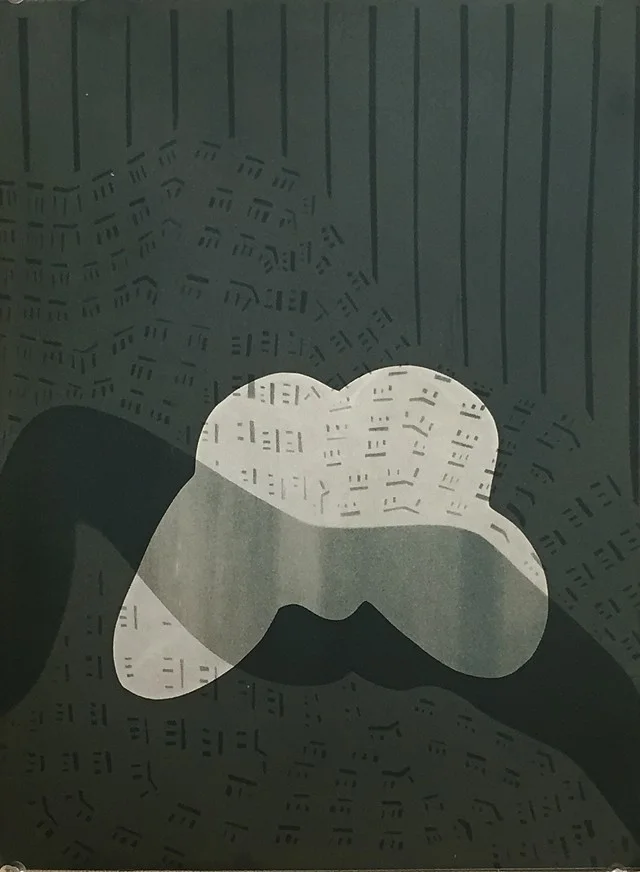

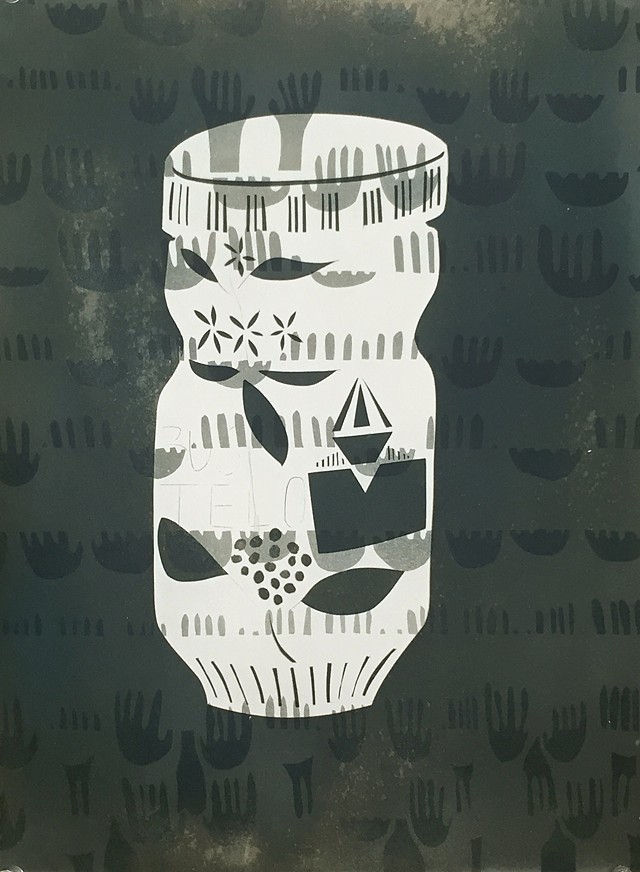

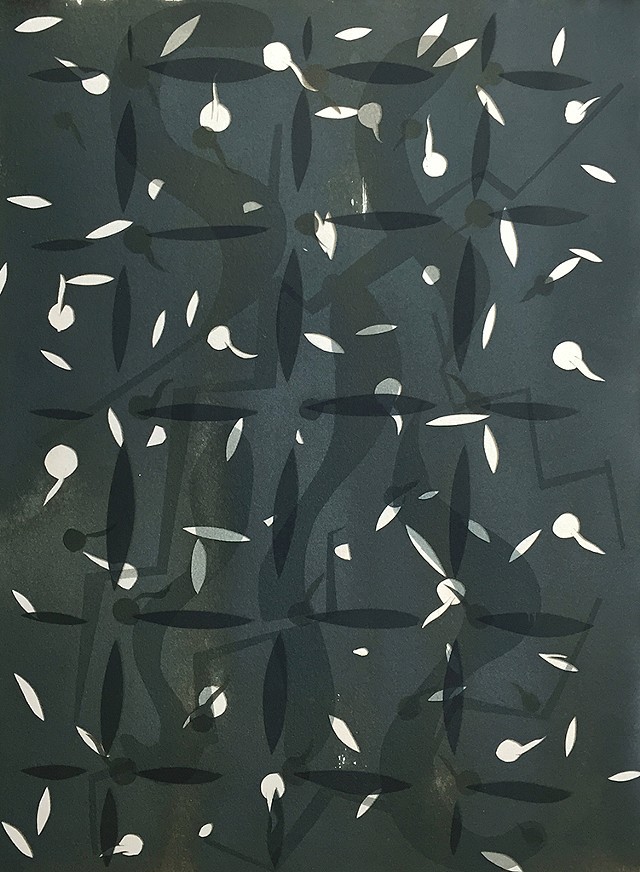

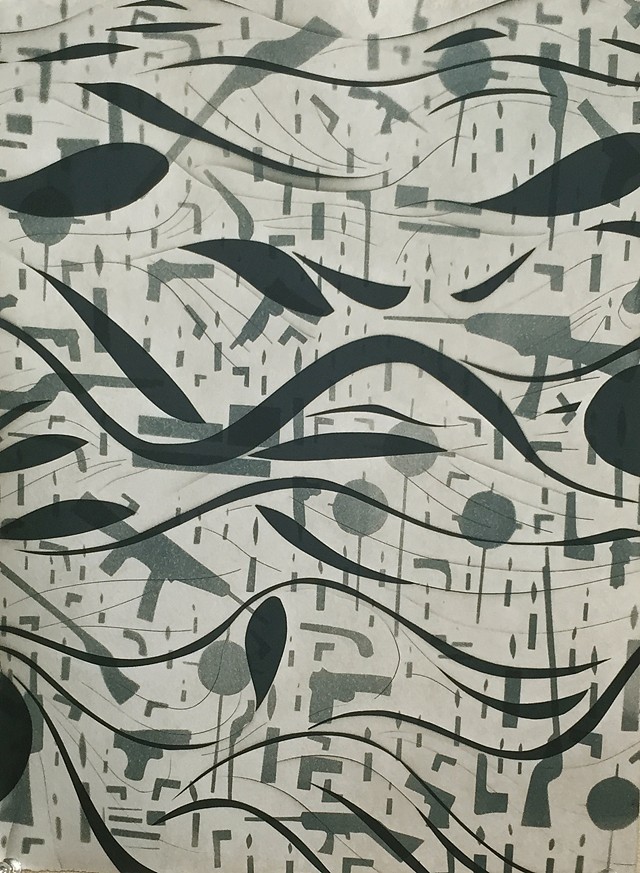

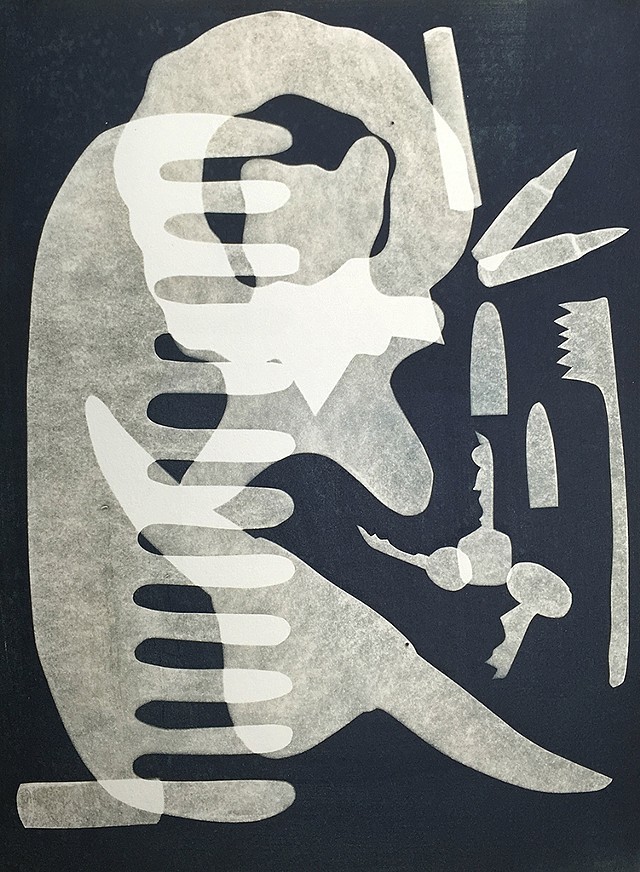

SERIES STATEMENT: "SHIT EATER"

This series of photographic prints focuses on the individual experience of navigating our increasingly complicated and counter-intuitive society. My current body of work is a good-natured parody of today’s world. The images are created as social commentary on current trends and events. I use the historical photographic process of cyanotype process and pair it with handmade negatives. Numerous exposures are layered on top of one another to complicate the visual space and to imitate our modern airwaves, full of news, headlines, gossip, Facebook feeds, Instagram feeds, twitter feeds, small talk, TV - but what is real? And what does it mean? These prints are made in response to feeling overwhelmed, and as an attempt to stave off feeling utterly helpless. I am interested in photography’s overlap with printmaking and painting. It is a very malleable medium that I think is often pigeon-holed into being just one thing. I want to see how far I can push it and what that exploration might find.

1. tell us about your hometown and how it shaped you artistically.

I grew up in Yorkville, NY, a small village right on the city line of Utica, NY. A friend from Philadelphia who recently drove through the area to attend a wedding, aptly described the old Rust Belt city as a “little big town”. It’s a small town, but a place with taller buildings and the facade of a bustling downtown. Back in the day it was a prosperous textile manufacturing hub but industry left long ago, leading to political corruption, organized crime and economic downturn in the 1950s. Upstate New York averages only about 100 days of sun per calendar year, and in my memories of it, it’s a quiet and empty place. Steady low cost of living has made it a melting pot for immigrants and refugees from war-torn countries, giving the place a hard-scrabble, worldly feel. In high school my friends and I would pile into one of their cars to go play soccer with the boys from Bosnia that we could not talk to, because we spoke different languages, but we could kick a ball with and sometimes kiss.

Growing up I was most comfortable on the sports field or taking pictures. I was quiet and both of those activities allowed me to communicate and to be social without saying too much. I was less interested in dating and drinking than my friends, but they let me participate by following them around with my camera. In “little big towns” like smaller, more rural towns, there’s a lot of space and time, and boredom. Photography gave me something to do and a reason to explore the abandoned factories, historic train stations, and locks of the Erie Canal. And shooting all those rolls of B&W film allowed me to spend many hours of the school day alone in the darkroom with my headphones on.

I liked growing up there. I love the smell of cut grass and the wooded edges. It wasn’t suburban, but it wasn’t urban either. The cloudy days suited me. And in a way it was what I, at the time, understood as a kind of American Dream. That in this place, with a stiff upper lip and long hours of hard work, things felt possible. You could stand and spread your arms. You could get lost, daydream and wonder, discover and plan and build. You were free to do what you like and whatever you please. In retrospect it likely felt this way to me as a teenager not because there was a wealth of opportunity, but a lack of scrutiny. No one was watching, it was a place that didn’t matter.

This experience of growing up, like growing up for many of us, is my foundation, the platform upon which the rest is built up. The sense of this place is something I carry with me. I prefer the windows of my studio to be open. I like dusty and worn wood floors, and lower light. I don’t like closed doors. I prefer my process to be physical rather than digital. I need to feel the film or the paper or what have you, to smell the chemicals, to stain my clothes. I need to experience the artmaking, to live it, to live through it. This ability to hold it in my hands, the tools, the materials, the finished product, allows me to call it my own. It is a way for me to mark my days, to claim my life. A kind of flag, I am waving, I am here, I exist. I matter. We exist. We matter.

2. as a multidisciplinary artist, which process have you felt most connected to and why?

At a frayed edge, if there is a thread, I tend to pull it. In my studio if there is a need to draw or paint, collect or build, or cut, I will do it, though my heart lies in photography and the work I feel happiest with comes almost always by way of a photographic process.

This comes from my early days of using the camera as a way to reach outside of myself and to explore the world around me. It was with the camera that I learned how to interact with the world, human and physical. It was with the camera I found a voice, my voice that says one thing, then another, always changing but never again forgotten or concealed or out of reach.

I still shoot B&W film, using a medium format camera, though that is not my primary mode of working. These days I tend to create images with photographic processes, more so than with photographic equipment, like the camera or darkroom or computer. My favorite photographic process right now being the cyanotype print, which creates an image in a tonal range of blues. This can then be toned to shift blues to tonal ranges of browns, and gray/black.

My enjoyment of this process comes, I think, from my early training in B&W photography to see light and tonal variations rather than color or color combinations. I am not as practiced in seeing color, these muscles are not as strong, so it is not my instinct to use them. I return again and again to the monochromatic. That is where I can push myself and find new ways of looking, of seeing, of showing to others.

3. your series focuses on the overwhelming nature of the modern world. how do you think information overload influences the creative process?

Getting older and growing up and taking on all the responsibilities that come with age, in a way, I feel like it’s not ever not surprising. Like you figure out how to fit it all in and balance it all out, and then something else gets added. Studio practice, even as a person who has dedicated my life to the arts and a career in the arts, gets pushed further and further away from the forefront. I look at that kind of experience as an individual experience. The micro experience of just trying to make it work.

Add on top of that the mezzo, your family and friends and neighborhood, and then the macro, politics and history and popular culture. And it becomes a cacophony, an overwhelming to-do list, should-do list, can’t-do list - - - OMG, what the fuck is that person- doing (?!?!) - list. And it can very easily turn into a moment where you throw up your hands and return to that micro experience of only worrying about yourself and just trying to make it work for you and close out all those other voices and concerns.

But that’s not going to work.

I want to hide from social media. I want to ignore the news. I want to pretend I can exist without considering my community or my city, my sexauity, my gender, my race, my class, but I can’t. That’s not going to work. That’s not going to make the world a place I want to live. That’s irresponsible. I can do more than that.

And so, that is how the overwhelming nature of the modern world affects my studio practice. Information overload influences my creative process similarly. It is a push and pull, a precarious balance between willing to fight and giving up. It becomes important to know when to turn off the podcasts, or to stop checking in with the Twitter or Instagram feeds, because it can start to feel like drowning and the act can shift from observing what’s going on out there and instead to getting sucked in. I want to be able to see inequity and inequalities (and the beauty too), but to stay just out of reach of popular culture and that instinct to fit in. Which, I think, is an instinct that can lead to blind eyes.

Outside of the quicksand that is social phenomena, information is a blessing and a curse. It can illuminate, but it can also destroy any possibility or opportunity of discovery or invention. So it becomes, again, all about that balance, knowing when to take things in and knowing when to shut the door.

4. having been both a teacher and a student, what are the pros and cons to having access to so many various forms of input at any given time? at what point does information cease to inform the artistic process and become a hinderance?

I love school and the classroom. I loved it as a student and, now, as a teacher. I love the loose, yet demanding, structure of higher education where you have all of these buildings and facilities that will allow you the space and tools to do what you want to do, yet there is a still a built in lunch period, and afternoon activities outdoors, and evening student groups canvassing everything from Model UN to Dungeons and Dragons. It is such a wonderful time of growth for the student. It is exhilarating. As a teacher, I get to engage with and encourage this energy, this forward momentum, which does encourage my own.

I have found in my years of teaching that being able to view so many different students work and hear so many different perspectives has helped keep my own studio practice and perspectives evolving. I am constantly challenged and forced to consider my thought process and beliefs. And sometimes, it’s not that serious, it will just be something small, like a student holding a tool in a different way that I never thought of, but makes so much sense.

The cons aren’t many. Much like anything else, it comes down to drawing boundaries and making sure you are keeping enough of yourself intact for yourself, and enough time and energy to pursue your own work.

So it is not about information being helpful or becoming a hinderance, but more about time and energy being allotted in a way that is sustainable for both the students and the studio to get what they need.

5. is this your first series pairing cyanotype with handmade negatives? how did you come to this process and what did it teach you about yourself as an artist?

I began working with cyanotype and alternative processes heavily under the mentorship of well-known alternative process photographer, Martha Madigan, while at my time in the MFA program at the Tyler School of Art, Temple University.

For several months in 2006, I explored using ortholith negatives to create prints that combine found images along with my own to create large works that I considered to be kind of collaged narratives. This way of working didn’t stick and at that time I went back to shooting with the medium format camera because I couldn’t figure out a good argument for why my photographic image was blue (cyanotype) or brown (vandyke brown print), or what have you.

I came back to the cyanotype process in 2014 when working on a collaborative project with artist Lewis Colburn. As members of the artist-run collective, NAPOLEON, we were participating as a group in CITYWIDE: A Collective Exhibition mounted by more than 25 artist collectives in the city of Philadelphia. Lewis is a sculptor and we had to figure how to work together with the idea that our concept for the exhibition would be multiples. We talked about how to look at things in more than one way. He “sees” things by building them in a three-dimensional form. How did I “see” things? At this time I wasn’t interested in interacting with his sculptures with the camera, which “sees” the light bouncing off of the subject the same way our eyes do, but rather trying to “see” his sculptures in a new way.

This is what turned me back to the cyanotype, which is a light-sensitive emulsion applied to a surface, usually paper or fabric, and then exposed by placing an object directly onto the surface of the sensitized material and putting it all under UV light. This creates a lasting impression of the thing you are exposing on the sensitized surface. You can use ortholith or digital negatives to create photographic images this way, like I was doing in 2006, or you can use the actual thing to create the image, called a photogram. When creating an image like this, you are not seeing the light that is bouncing off of the subject, instead you are seeing the light that is falling all around the subject, or pushing through the subject. This is what hooked me to the process, being able to see these things in a new way, a way that was true, just as true as the way my eyes saw it, but in a way that I could not see with my eyes alone. (And I use that word “true” in the most gentle of ways. I know truth is a slippery slope. I mean only the idea of the truth in the fact of the way that light falls.)

After completing this project with Lewis, I continued working with the medium and exploring ideas and concepts that were important to me. By creating photograms of objects, instead of using negatives I no longer felt the need to defend the blue or brown photographic image and instead could get comfortable and invested in exploring form, composition and content. Moving through phases of using different found and collected objects, I tried many different ways of creating images that spoke to the ideas I was trying to share, the current evolution of this process being creating exposure with handmade negatives.

I think, in a way, kind of coming back full-circle as a photographer, wanting to create and be in control of many aspects of the image, and wanting to be able to fall back on the negative for the creation of multiples or multiple attempts. The creation of these handmade negatives is also in line with my desire to interact with the process of artmaking in a physical way.

Unlike many aspects of digital photography, working with film or alternative photographic processes still has many moments of mystery and instances of things not working out the way you thought it would. What working this way has taught me about myself as an artist is that I delight in those moments that are just out of reach, those ideas that I can only plan up to a certain point but whose final outcome will be something unexpected. I enjoy building on these discoveries and working under the guise of control, when really I am not.

6. when did you begin working with photography? was it something you explored independently (prior to obtaining your degrees) or did you take classes as a child?

I came to photography in high school after a knee injury sidelined me from a season of soccer. I was always in art classes in school, focusing mostly on drawing, but soccer was always competing for my attention. At 15 with a torn ACL, I was furious and felt trapped by my failing body. Sports had been such an important way for me to work out emotional distress or tension and to connect with my peers, and now I didn’t have it. Drawing at that time felt so slow and careful - where photography garnered fast results. It was more active, and a means of exploration and adventure. I signed up for Intro to Photography in my sophomore year of high school and had a wonderful photography teacher, Mr. Cost, who let me work at a fast and furious pace for the rest of my high school years, even allowing me access to equipment over the summers. He provided me with a camera and endless rolls of film, endless encouragement, and a hands-off approach to content. Though he was always quick and direct to tell me when something was “crap”, which only pushed me harder.

7. what has creating autobiographical content helped you to understand about yourself and your environment?

Working with autobiographical content has allowed me to have a better understanding of my character and who I want to be in the world. It has helped me to create clearer convictions and to determine what’s important to me and what’s not. It has allowed me to work through experiences or relationships that were troubling to me and celebrate those that were inspiring and supportive. Creating autobiographical content through photography has offered me a way to explore my surroundings, social and physical, and to better understand my place in these environments.

8. what kind of materials, spaces, or experiences do you seek out to restore your creative output?

Every summer I create a situation where I can leave the city and my responsibilities and take my camera and go shoot. I always use my medium format Mamiya and B&W film. These rolls are often, if not always, outside of the scope of my current body of work or work-in-progress. In this way they are an escape, a reset or a pause button, a time-out to just get back to the basics of observing light and finding inspiration in the observation of subjects and the discovering of pleasing compositions.

More regularly, when I can, I have the routine that once the morning chores are done and my wife leaves for work, I sit in the kitchen and listen to the morning news and eat breakfast with my dog.

It is also important for me to get out to the woods regularly and at least three times a week I ride my bike from where I live in Fishtown, on the East side of the city, west out to Kelly Drive and the Wissahickon Park, which is a wooded area off of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia.

9. how has your work evolved since you began working as an artist?

Since picking up the camera at 15 my work has become more confident, more experimental and more abstract. As an artist I don’t feel confined to one medium or one way of working. I am willing to take more risks and to stand behind them, to gleefully celebrate the mess that sometimes comes with experimentation.

10. any upcoming projects or shows we should know about?

I am in the midst of working on a number of different projects, some of which are too new and their final form too illusive to introduce at the present. However, what I can share is that I will have a new series of cyanotype prints on display in a solo exhibition at Tallahassee’s 621 Gallery in May 2017, which will deal with ideas of shelter. And my current body of work, which I have presented to you here, will continue to be a work-in-progress and will be on display as a solo exhibition as a part of The Fleisher Art Memorial’s Wind Challenge Exhibition Series in Philadelphia sometime in 2017/18 (Date still TBD.)

Tamsen Wojtanowski is an artist living and working in Philadelphia, PA. She received her BS from Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY and her MFA from the Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. Her work has been included in recent exhibitions at Artist-Run, The Satellite Show, Miami, FL; COOP Gallery, Nashville, TN; Soil Gallery, Seattle, WA; Lux/Eros Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; and The Black Box Gallery, Portland, OR. She has taught at Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA; Arcadia University, Glenside, PA; and the Corcoran College of Art + Design, Washington, DC. She was added to Fotofilmic’s Shortlist 2016, and was a top ten finalist in The Print Center’s 89th International Juried Competition in 2015. She is a founding member of the artist-run exhibition space NAPOLEON, Philadelphia, PA.